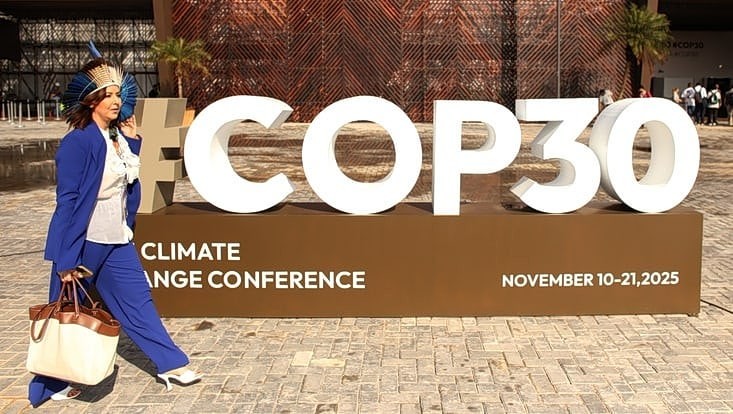

World Climate Conference“Belém is a Signal”

10 November 2025, by Thomas Merten

Photo: Raimundo Pacco/COP30

This year, the world is heading to the Amazon for the UN Climate Conference. Sociologist Eduardo Gonçalves Gresse from the Cluster of Excellence CLICCS at the University of Hamburg is originally from Brazil and will attend COP30 in Belém as a researcher. He explains why the conference gives him cautious optimism, what Brazil can contribute to global climate governance – and what he himself is looking for between rainforest, civil society, and science.

Prof. Dr. Eduardo Gonçalves Gresse. Foto: Privat

Professor Gresse, you’re traveling to the UN Climate Conference in your home country, Brazil. What does that mean to you?

I’m very glad that the COP is taking place in Brazil. After years of multiple crises and an anti-ecological backlash under Jair Bolsonaro, President Lula da Silva announced that the next conference would be held here, in the heart of the Amazon. It’s a political signal – a way to bring Brazil, with its strong diplomatic tradition and leadership in global environmental politics, back onto the international stage.

Why Belém, specifically? What makes the city special?

Belém is a vibrant, multicultural metropolis at the edge of the rainforest. I was born and raised far away in São Paulo but visited the area as a child. It feels like a different world, even just in terms of food. Belém offers an incredible variety of fruits and ingredients you won’t find elsewhere in Brazil – or the world. Its local art and culture are equally fascinating. At the same time, the city, like many large Brazilian cities, is marked by deep social inequalities.

Many people outside Brazil probably don’t even know this city, unlike Rio or São Paulo.

Exactly. And Belém is hardly prepared for a mega-event like the COP. When infrastructure is built in a rush without involving local communities, it can easily deepen existing inequalities. There are also concerns about the environmental impact of the event itself. Yet for many Brazilians, the COP in Belém is also a symbol of renewal. It sends the message to the world that the Amazon is not just an abstract green space on a map but home to millions of people and cultures.

What role does Brazil play in international climate politics?

For decades, Brazil held a strong diplomatic position as a mediator between the Global North and South. During the Bolsonaro years, the country fell into a kind of political vacuum. Bolsonaro didn’t dare to withdraw from the Paris Agreement – there was nothing to gain from it – but his government effectively worked against everything the agreement stands for. President Lula is now trying to restore that traditional role. Yet while deforestation has decreased, oil exploration is about to increase. Lula says he wants a world without fossil fuels “one day,” but he’s also realistic: the world isn’t ready to live without oil. That shows Brazil’s ambivalence. On one hand, the COP30 team led by diplomat André Corrêa do Lago is highly competent and aims to strengthen international cooperation and climate finance. On the other, Brazil remains a major oil producer, and its environmental policies are constantly under attack.

Cidade de Belém, capital da Cop30 Amazônia. Foto: Rafa Neddermeyer/Cop30 Amazônia

What will you be doing in Belém?

I’ll be at both the official COP and the Cúpula dos Povos, the civil society summit held alongside it. Brazil has a long tradition of such spaces – from the Rio Conference of 1992 to the World Social Forum in 2001. For me, these connections between politics, research, and civil society are what make Belém so exciting.

What exactly are you researching there as a sociologist?

Our international team from Brazil, France, and Germany is conducting what we call a collective ethnography. We’ll be observing the conference itself – the negotiations, the rituals, the promises. How do they emerge, and what power do they hold? I’m particularly interested in how Brazil performs its leadership role and how the global goal on climate adaptation is negotiated and implemented. Adaptation is far more complex than reducing emissions because it is always in-the-making and must respond to local realities – such as those in the context of flooding, extreme heat, drought.

So far, many COPs have struggled to deliver results. What’s your outlook this time?

I feel a kind of skeptical hope that COP30 could really be the “COP of implementation,” as Lula and the COP President have promised. At the General Plenary of Leaders in Belém, Lula himself has said that we needed a way to reverse deforestation and to overcome our dependence on fossil fuels in a planned and fair manner, and to mobilize the resources needed to achieve these goals. For this to be realistic, it would be important to build new alliances – especially now, in a time of crisis for multilateralism. The USA currently opposes and even obstruct climate politics, there are wars, tensions, and setbacks. That makes it even more important for countries like Brazil to act as mediators and to show that international cooperation for climate protection and justice is still possible.

What can the host country realistically achieve?

The Brazilian government now has the chance to take marginalized voices seriously and include them more directly in climate policy – precisely because the country itself stands between development and sustainability. And I hope that civil society and Indigenous groups will truly have a seat at the table. It’s expected that more representatives of Indigenous communities will attend than ever before.

But will they be able to influence the negotiations?

This time there will likely be more space for civil society actors – but it will never be enough. Participation is always a struggle. What’s encouraging, though, is that Brazil’s civil society remains strong, alert, and vocal. Networks such as Observatório do Clima are even suing the government over new oil exploration projects at the mouth of the Amazon River.

You’re also engaged beyond academia.

Yes, I co-founded a Brazilian NGO called Instituto Terroá, which is celebrating its tenth anniversary this year. During the COP, I’ll give a talk on climate futures and present our key study on adaptation, the Hamburg Climate Futures Outlook 2024. I was invited to help bridge science and civil society – to practice a kind of public sociology. For me, it’s not only about research, but about engagement.

What do you hope to bring back to Hamburg?

Many things, but above all a renewed connection to the Amazon’s reality. We often talk about the environment from a distance. Being there makes you part of it – the heat, the people, the biodiversity, all of it. That changes your perspective. It reminds me that research is not just analysis, but relationship: to places, to people, to indignation and solidarity, to diverse ways of knowing.

So more than just data and notes.

Yes – maybe that Brazilian sense of joy and community. Despite all its contradictions and problems, the country has a special way of making people feel welcome. That’s something the international climate negotiations could use more of – a sense of belonging. If I bring anything back, it’s that: even in times of crisis, it’s possible to create spaces where people feel connected and empowered.

More information

Eduardo Gonçalves Gresse is a sociologist and currently Acting Professor at Universität Hamburg. His research focuses on how societies respond to climate change and which social factors enable or hinder transformations toward sustainability. He also studies how diverse ways of knowing – including Indigenous knowledges – can be integrated into climate research and policy. As co-editor of the Hamburg Climate Futures Outlook, he develops methods to assess the social plausibility of climate futures. Gresse is co-founder of the Brazilian NGO Instituto Terroá, which supports local sustainability initiatives.